During the construction of the museum on the Itumbaha Bihara, numerous allegations and interpretations were raised by various national stakeholders. Many expressed dissatisfaction with Rubin’s involvement in the museum’s development. Differing viewpoints both supporting and opposing the case were reported in various newspapers.

As a result, the team from Khojpatra conducted a round-table discussion with three key individuals: Swasti Rajbhandari Kayastha, a lecturer of museology at Lumbini Buddhist University; Jorrrit Britschgi, the Executive Director of The Rubin Museum of Art; and Pragya Ratna Shakya, the Chairperson of the Itumbaha Conservation Society. This article has been prepared based on insights gathered from their conversation.

During 2022, an image of Apsara with a garland dating back to the 14th Century was successfully repatriated to the Itumbaha premises. This artifact had disappeared from its original location in the late 1990s and was later discovered as part of the Rubin Museum collection in the early 2000s.

Subsequently, when a claim supported by sufficient evidence was made for its rightful ownership, the artefact underwent the standard repatriation procedure and was returned to its original location at Itumbaha.

During the repatriation discussion, Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha, a lecturer specializing in Museology at Lumbini Buddhist University, participated actively. It was during this event that she was introduced to Pragya Ratna Shakya, the president of the Itumbaha Conservation Society. Notably, Mr. Shakya not only resided permanently in Itumbaha but also played an integral role in various ceremonies conducted in the area. Over time, he had envisioned the establishment of a community-led museum within this space.

Upon meeting Ms. Kayastha, Mr. Shakya enthusiastically shared his idea of creating such a museum, engaging her in the exchange of thoughts and aspirations for the future project.

Mr. Shakya had already been in communication with relevant government officials, including Mr. Bidhya Sundar Shakya, the former mayor of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City. During their meetings, the mayor verbally pledged to provide one crore in support of the museum’s opening. However, despite the assurance, the promised financial aid never materialized.

Meanwhile, a rumor began circulating, suggesting that the Itumbaha community lacked a viable plan to utilize the allocated budget effectively.

According to Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha, who spoke with the team Khojpatra, there were ongoing discussions about the museum’s opening. However, she noted that the team itself seemed uncertain about how to initiate the process, mainly because many individuals in the Itumbaha community lacked knowledge about the budget and time required for the museum’s establishment.

While repatriating the image of Apsara, the representatives from the Rubin Museum expressed their interest in providing further support to the monastery in any manner they could. During one of their conversations, the concept of a community-led museum was put forward. However, the practical implementation of this idea raised the question of “how” to proceed.

As a result, a collaborative partnership was established among the Itumbaha Conservation Society, the museology program at Lumbini Buddhist University led by Ms. Kayastha, and the Rubin Museum of Art. This partnership aimed to offer advisory and financial assistance for the documentation, preservation, display, and interpretation of Itumbaha’s historical collection. Through this joint effort, the vision of a community-led museum started to take shape.

Having studied in the United Kingdom and received training in museology, Ms. Kayastha was entrusted with the role of curator for the Itumbaha Museum. This appointment brought forth numerous challenges in the planning and decision-making process. She had to balance adhering to standard museum practices while also considering the opinions and sentiments of the community members.

As her first community-led project, this opportunity provided her with valuable insights into the power of community involvement. To aid in the endeavor, Ms. Kayastha engaged two of her students in the project. Together, they collaborated on tasks such as cleaning, displaying, and crafting narratives for the exhibits in three different languages: Nepali, Newari, and English.

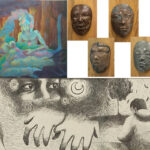

The museum’s collection comprises a wide array of artefacts, including oil lamps, crowns adorned with precious stones, ancient bells, and even a smaller version of a Stupa delicately embroidered with valuable gems, among many others. Mr. Shakya reveals that the museum holds more than 500 artifacts in total, but due to budget constraints, only around 150 of them are currently on display.

He explains that within the Vajrayana tradition, numerous items used during ceremonies are shrouded in secrecy and unveiled only once a year. However, as time passes, the knowledge of their significance and purpose is not adequately transmitted from one generation to another.

To address this issue and illuminate the historical and cultural significance of these artifacts, the Itumbaha Museum strives to showcase and preserve their rich history for the appreciation and understanding of present and future generations.

Since its inception in 2004, the Rubin Museum of Art has remained a steadfast supporter of Himalayan Art. Jorrit Britschgi, the Executive Director of the museum, emphasizes that beyond merely exhibiting artifacts, the museum actively promotes Himalayan artworks and artists. Additionally, the museum extends its assistance to artists from the Himalayan diaspora, aiding them in shaping their narratives in the contemporary world. This ongoing support and involvement have been widely recognized and appreciated.

In Jorrit’s words, the current aid provided to Itumbaha is solely aimed at establishing the museum. The Rubin Museum does not expect anything in return and is content that the community will take on the responsibility of managing the museum in the future. However, Jorrit reassures that should the community require further assistances; the museum will always be there to lend its support.

According to Jorrit, “the artifact we possessed was purchased through an auction in the American market.” After its acquisition, the museum exhibited it, but they subsequently received claims asserting its origin to be from Nepal. In response, the museum conducted a comprehensive investigation into the provenance of the artifact and, as a result, decided to repatriate it to its rightful place in Nepal.

Jorrit further explains that there might be other artifacts in the museum’s possession obtained from various parts of the world through purchases in the USA. However, he emphasizes that if proper legal procedures and documentation are provided to the museum, they would be more than willing to repatriate those artifacts in the future.

Addressing the protest concerning their participation in the Itumbaha Museum project, he clarifies that the Rubin extended their hand for support. He asserts that their involvement won’t be direct, implying that they won’t take control of the project. Instead, their role is that of a supportive entity.

Furthermore, he emphasizes that the community holds the primary responsibility as the museum’s guardian and for safeguarding its precious artifacts. The museum’s success and preservation lie in the hands of the community.

Nepal can be likened to an open museum, but the concerning lack of organization within these museums is becoming more apparent in the media. The inadequate protection and management of our valuable heritage sites have been a prominent issue receiving increasing attention.

Given the insufficient financial support from within the country, seeking external assistance becomes essential to address the challenges. The question arises as to how a future museum can be established amidst Nepal’s archaeological heritage areas. The successful handling of this endeavor will rely on the expertise and resourcefulness of Nepali skilled technicians. The way they approach and overcome this challenge remains to be observed.

Additionally, the management of scattered and damaged archaeological materials within these heritage areas presents a pressing concern. How these issues are addressed will serve as a reflection of the extent of national and international cooperation in the future days.

Leave A Comment